Reflections on

Memories of Home

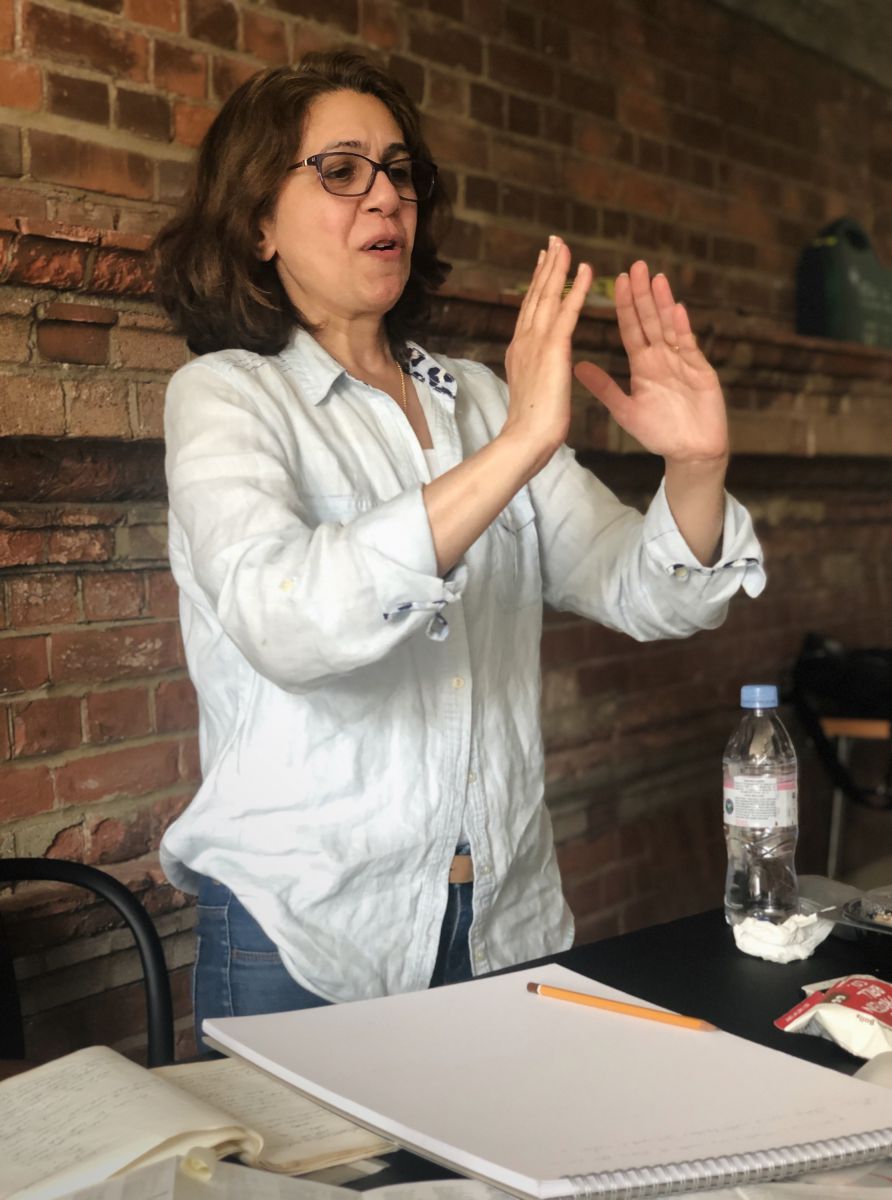

The following text presents reflections on a participatory workshop titled Memories of Home which engaged women of the Iraqi and Arab diaspora in London in dialogue and discourse around perceptions of identity as related to place, history and memory. Participants were asked to select an object of sentimental value that they, or their family members, brought with them from their home country. These objects, fragments and memorabilia of the past, served as anchors of memory and history, acting as portals that transported us across spatial and temporal boundaries.

Through this initial exploration of the relationship between the objects and the histories and memories which embed them with meaning and value, the group engaged in individual and collective contemplation on the varied and often conflicting experiences of displacement and their reverberating impacts across multiple generations.

The aim of the workshop was to encounter, extract and record individual narratives to produce a series of written, oral, and visual recordings that describe tensions associated with the loss of, and longing for ‘home’.

Our gathering brought together a group of women with a varied set of experiences in relation to displacement. Some shared first-hand experiences living in and leaving their homeland, while others left quite young or were born in the diaspora and contributed ‘inherited’ or ‘imagined’ narratives. Reflecting back, what unites them is a shared sense of longing for a construct of a home that they’ve either lost, or never known.

Through a constructive engagement with the past, we worked towards reclaiming a sense of ownership over their personal and collective experiences.

Nedal’s (b. Iraq) month-long vacation to London in 1979 has lasted 41 years. She has spent the majority of her life in exile; “All is gone, except the memories kept in the little items we carried with us.” She met her husband and raised three daughters in England. “I am proud of my daughters because they are connected to their homeland, but we didn’t force it upon them, and we gave them the freedom to decide for themselves.” Her daughter Rayya (b. 1988, UK), also part of the group, acknowledges the role her parents played in her conceptualization of Iraq but describes developing an interest in the culture and politics in Iraq independently. She is now a leader within the Iraqi Association and CAFI (Collective Action for Iraq), and an instrumental partner to this project.

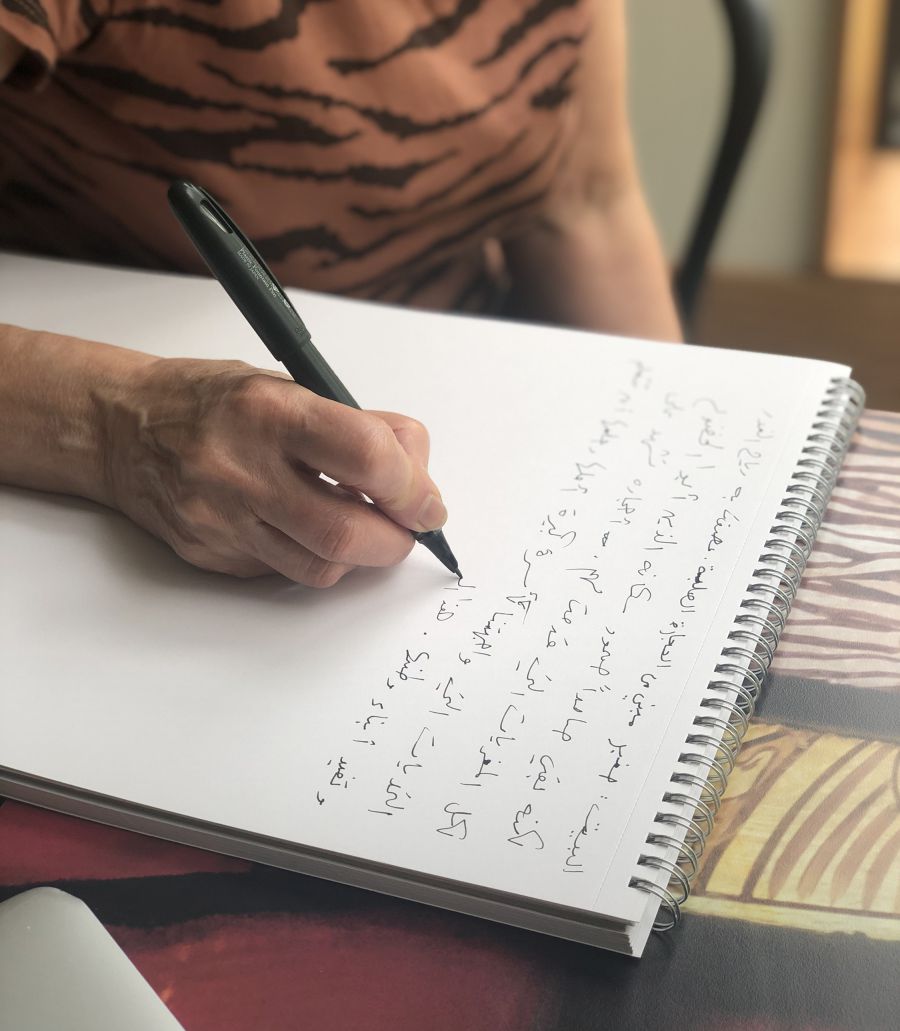

Entissar (b. 1954, Syria) moved to London only three years ago. Through an organization called Scheherazade Initiatives, which organizes theatre-based workshops and projects for community groups, she has used writing and acting to express her experience of displacement. “Home, no matter how far away we drift, remains in our heart through its memories, both bitter and sweet. We cannot separate the past from the present, there is always a thin line that connects them together. There are simple things that pull us to the past, like loving a flower because my mother used to like it or liking a certain dish because it reminds me of my sister or my aunt. This thin line, however thin, is strong and stable and, in god’s will, won’t break.”

Hear Entissar speak about the past and the present

Ashtar (b. 1961, UK), a filmmaker born to an Iraqi father and British mother, describes her Iraqi experience as ‘less distilled’. “I didn’t grow up with my father, but I was always fascinated by him and the country that he’s from.” It was only as an adult, having reconnected with him, that she started to get better acquainted with that side of her identity and family history. Her film, Abdallah and Leila (2017), is an imagined retelling of his experience. Ashtar recalls her father’s memory by attempting to understand who he was as a young man in Iraq and speculating on his experience as an older person living in a foreign country and battling dementia. “The film was my first attempt at exploring what being an Iraqi meant to my father, I suppose. It’s more about what I imagined my father to be thinking. It’s speculating, which as a second generationer, you do quite a lot of.”

Maysoun (b. 1954, Iraq) moved to London twenty years ago. She demonstrates a strong sense of dedication towards public service and is genuinely interested in connecting with people. “One can never forget the past, neither the hardships nor the pleasure, especially pleasant memories with family, friends, and neighbours, they cannot be replaced… And I pray to god that he preserves my memory and the memory of everyone else. With these beautiful memories you will continue to live and prosper. Looking back warms you and makes you reflect on how wonderful those times were, especially these days when Iraq’s condition is deteriorating, it will be painful for us.” Throughout the sessions, her voice was the sound of wisdom and encouragement. Her words carefully chosen, inspired, and always optimistic.

Our dialogue emerged from an initial exercise where participants were asked to describe their selected object solely through the memory or meaning it holds for them. It offered an opportunity to reflect on and renegotiate our relationship to our personal, familial, and collective histories.

Rather than accept the preservation of history and memory as an imperative duty, we debated and interrogated its true value within our lives, some of its more painful attachments, and how that pain (or knowledge, as we later came to call it) carries forward across generations. The objects became vessels through which we were able to access and examine personal attitudes towards remembrance.

Shezza’s (b. 1985, Syria) object is directly associated with the memory of leaving her home country of Syria as a young child. “The memory behind it is probably the oldest thing I own which came with me from Syria…it took the journey with me, and it’s taken the journey with me throughout my life every time I have moved.” Shezza later reveals her object to be a set of miniature glass turtles from her childhood, one of the few items she could fit into the small bag of favourite belongings her mother asked her to pack before having to suddenly flee the country. “They represent a lot of things, even in a metaphorical way. The idea of carrying your home on your back as a little turtle. When you see baby turtles crawling on the sand trying to get to the sea… the journeys of migration.”

Rayya’s object is one she “inherited” rather than brought from Iraq. “By inherited, I meant borrowed it and never gave it back. I was told the story about it afterwards, so I carried that story with me. It’s weird, like having a flashback and almost imagining the beginning of its story. This is how I describe the imagined memory. It has become a part of me. It is with me almost all the time and like what Shezza said about the journey, I feel I am part of its journey, because it has made its journey over here before me and I am continuing with it and I take it on my journeys as well.”

The group examined some of the themes explored within Larissa Sansour’s film, In Vitro, which centers around a conversation between a young woman and her mother on trauma, nostalgia, and history’s heavy burden on younger generations. Shezza posits,

“Do we live the dream of our parents, or do we live our own dreams?”

For Arwa (b. 2002, Iraq), a more idealized retelling of history is required. “Sure, it’s our heritage and our history, but some sad and miserable memories shouldn’t be passed on to the next generation. Why do you burden them with this pain and this sad history and pass it onto another generation, is it necessary?”

Asmaa (b. 1991, Iraq) responds; “I think a big part of the conversation is that it’s not on purpose. It’s not on purpose that some things are passed on. There are intergenerational traumas that are passed on, and I see it even through the way my father internalizes his experiences.”

“Of course, we feel guilty sometimes,” says Nedal, “because they (her daughters) were hurt too, they’ve carried the pains and struggles of a country troubled with worries, war and siege. They felt it, and I felt guilty because I had to keep them away, but I couldn’t, and I didn’t plan it.”

Hear Nedal speak about guilt

Rayya describes the pain as being two-fold; “For the first generation, their pain comes from direct experience, but for us it is the pain of seeing what our parents have been through. It’s a different kind of pain, almost a guilt that we didn’t have the direct experience. Also, a responsibility, because we’ve inherited these things, we have to protect them and there is going to be a time when we lose the previous generation and we’ll have to hold on to these memories for them, and the same for us after we’ve gone.”

Even as someone who has directly experienced the traumas of war, Zainab (b. 1995, Iraq) still feels that she has ‘inherited nostalgia’. “I was eight years old during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, so there wasn’t even a nation for me to lose. There was only war and chaos. You speak of an Iraq that is completely different from the one that I see. Although I want to go (back), I feel that exile is a permanent state and that once you leave, you will never return. My Iraqi identity is a very essential part of my existence and it means a lot to me, but when I have a child, they won’t have that strong connection with Iraq that I had. Enforcing it would harm that person. I will be projecting many things on them that they will neither experience nor understand, and they will always remain abstract and intangible.”

Although it hurts; for Rayya, the transfer of that pain is still important. “Without pain, how will we learn, how will we remember? Maybe without pain, we would not have had the same sense of longing to our homeland. Maybe it’s the pain that will drive us to continue to connect and do positive things for wherever we’re from.”

“Maybe we don’t need to call it pain,” says Asmaa “but think about it more as knowledge, of our history and the context surrounding how we got here. This transfer of knowledge is a way for us to understand where we stand, and how we can use our privilege where we are needed the most.”

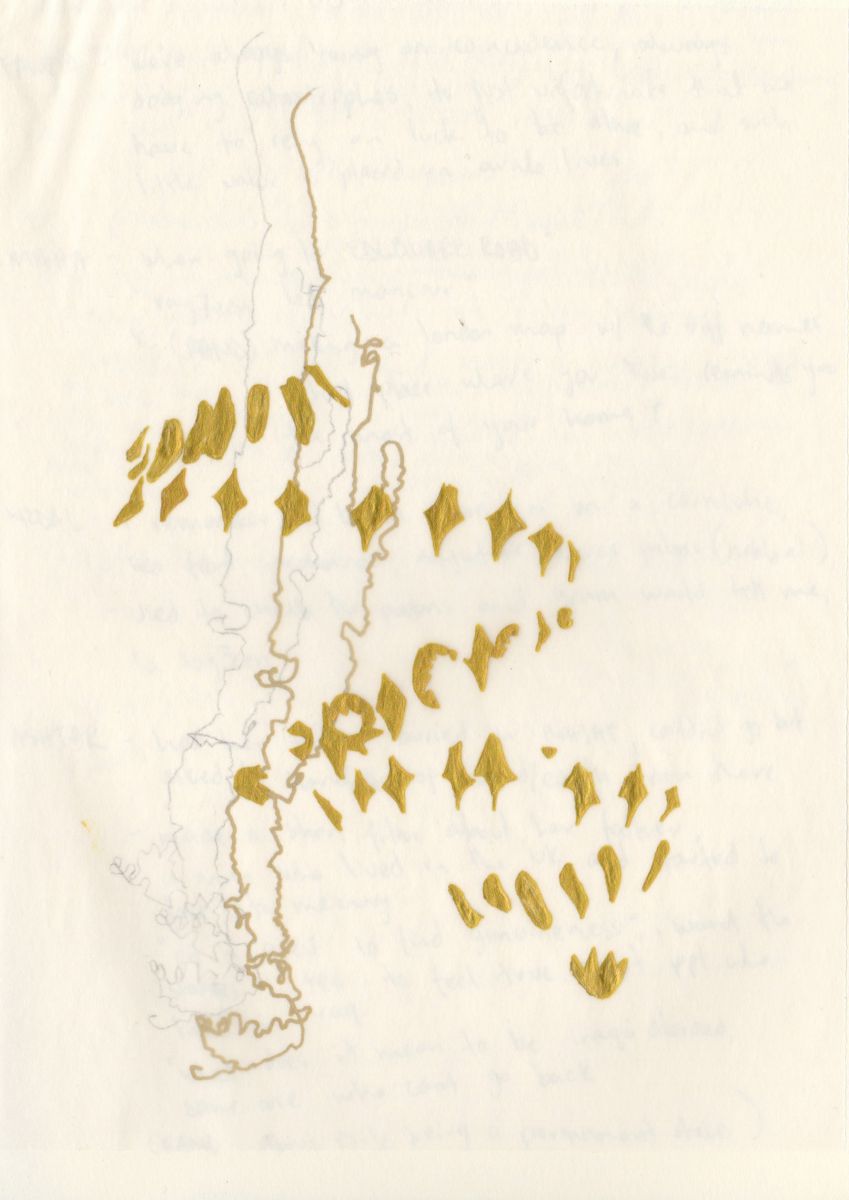

Shifting our perception of pain towards that of knowledge generates historic currency; a newfound agency to lay claim to our own narratives. One person’s past becomes their community’s history. Documentation of this individual knowledge thus becomes essential to our ability to communicate our collective narratives and push back against contemporary misrepresentations of our culture in the media.

These themes are saturated within the work of Irish-Iraqi visual artist Basil Al-Rawi, who joined us as a guest speaker to discuss how photography and memory have framed his practice, and particularly his Iraq Photo Archive project. The Iraq Photo Archive invites Iraqis to submit scans of their family photographs and share descriptions of the people, places and stories that they capture.

The ‘archive’, in its framing of history, is very much a political tool. Some of the most important photographic records of Iraq are held by institutions such as the Library of Congress and the Royal Geographic Society, or are situated within personal collections such as the Gertrude Bell Archive, and are all tinted by a colonial gaze. What I appreciate about the Iraq Photo Archive is its attempt at the decolonization of historic narratives, empowering people with the agency to narrate their individual stories outside any particular political agenda - and with time, composing a larger collective history.

This brings us back to the intended outcomes of this workshop – to produce a series of recordings, fragmentary reconstructions of personal experiences, that start to reveal these tenuous threads Entissar describes which maintain our emotional connections to a construct of home.

What is our responsibility towards communicating our experiences, and in what form does our legacy take shape?

Explore a collection of recordings produced by the participants in which they recount personal meditations on memory, displacement, and the various shades of diasporic experience.